Facebook announced today that it had banned the app myPersonality for improper data controls and suspended hundreds more. So far this is only the second app to be banned as a result of the company’s large-scale audit begun in March; but as myPersonality hasn’t been active since 2012, and was to all appearances a legitimate academic operation, it’s a bit of a mystery why they bothered.

The total number of app suspensions has reached 400, twice the number we last heard Facebook announce publicly. Suspensions aren’t listed publicly, however, and apps may be suspended and reinstated without any user notification. The only other app to be banned via this process is Cambridge Analytica.

myPersonality was created by researchers at the Cambridge Psychometrics Centre (no relation to Cambridge Analytica — this is an actual academic institution) to source data from Facebook users via personality quizzes. It operated from 2007 to 2012, and was quite successful, gathering data on some four million users (directly, not via friends) when it was operational.

The dataset was used for the Centre’s own studies and other academics could request access to it via an online form; applications were vetted by CPC staff and had to be approved by the petitioner’s university’s ethics committee.

It transpired in May that a more or less complete set of the project’s data was available for anyone to download from GitHub, put there by some misguided scholar who had received access and decided to post it where their students could access it more easily.

Facebook suspended the app around then, saying “we believe that it may have violated Facebook’s policies.” That suspension has graduated into a ban, because the creators “fail[ed] to agree to our request to audit and because it’s clear that they shared information with researchers as well as companies with only limited protections in place.”

This is, of course, a pot-meet-kettle situation, as well as something of a self-indictment. I contacted David Stillwell, one of the app’s creators and currently deputy director of the CPC, having previously heard from him and collaborator Michel Kosinski about the dataset and Facebook’s sudden animosity.

“Facebook has long been aware of the application’s use of data for research,” Stillwell said in a statement. “In 2009 Facebook certified the app as compliant with their terms by making it one of their first ‘verified applications.’ In 2011 Facebook invited me to a meeting in Silicon Valley (and paid my travel expenses) for a workshop organised by Facebook precisely because it wanted more academics to use its data, and in 2015 Facebook invited Dr Kosinski to present our research at their headquarters.”

During that time, Kosinski and Stillwell both told me, dozens of universities had published in total more than a hundred social science research papers using the data. No one at Facebook or elsewhere seems to have raised any issues with how the data was stored or distributed during all that time.

“It is therefore odd that Facebook should suddenly now profess itself to have been unaware of the myPersonality research and to believe that the data may have been misused,” Stillwell said.

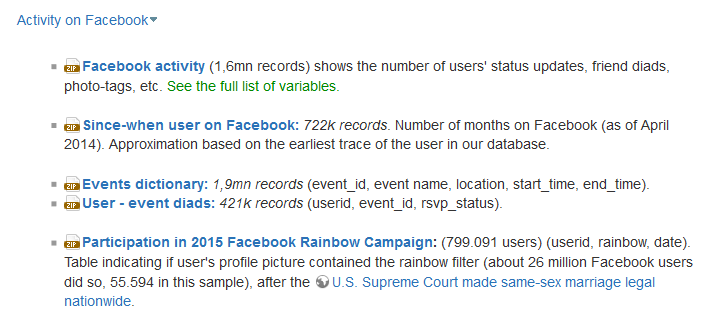

Examples of datasets available via the myPersonality project.

A Facebook representative told me they were concerned that the vetting process for getting access to the dataset was too loose, and furthermore that the data was not adequately anonymized.

But Facebook would, ostensibly, have approved these processes during the repeated verifications of myPersonality’s data. Why would it suddenly decide in 2018, when the app had been inactive for years, that it had been in violation all that time? The most obvious answer would be that its auditors never looked very closely in the first place, despite a cozy relationship with the researchers.

“When the app was suspended three months ago I asked Facebook to explain which of their terms was broken but so far they have been unable to cite any instances,” said Stillwell.

Ironically, Facebook’s accusation that myPersonality failed to secure user data correctly is exactly what the company itself appears to be guilty of, and at a far greater scale. Just as CPC could not control what a researcher did with the data (for example, mistakenly post it publicly) once they had been approved by multiple other academics, Facebook could not control what companies like Cambridge Analytica did with data once it had been siphoned out under the respectable guise of research purposes. (Notably, it is projects like myPersonality that seem to have made that guise respectable to begin with.)

Perhaps Facebook’s standards have changed and what was okay by them in 2012 — and, apparently, in 2015 — is not acceptable now. Good — users want stronger protections. But this banning of an app inactive for years and used successfully by real academics for actual research purposes has an air of theatricality. It helps no one and will change nothing about myPersonality itself, which Stillwell and others stopped maintaining years ago, or the dataset it created, which may very well still be analyzed for new insights by some enterprising social science grad student.

Facebook has mobilized a full-time barn door closing operation years after the horses bolted, as evident by today’s ban. So when you and the other four million people get a notification that Facebook is protecting your privacy by banning an app you used a decade ago, take it with a grain of salt.

source https://derekpackard.com/facebook-bans-first-app-since-cambridge-analytica-mypersonality-and-suspends-hundreds-more/

No comments:

Post a Comment